A few weeks ago, I gave a talk to the AP Physics class at my old high school about why they should all study physics in college. I tried to just focus on the experience of being a physics major in college. Explaining why physics itself is interesting or talking about careers/graduate school would have made my talk too long. Although the main message of my talk was obviously physics-centric, I tried to make it as widely useful as possible. Regardless of what major you may be considering, you should ask yourself all of the following questions:

- Will I stay interested in this subject for four years? (Unfortunately, this is one is pretty tough to answer.)

- Are there happy and satisfied people who have traveled the route I am thinking about taking? (This doesn’t guarantee that you’ll be happy, but it at least lets you know that you could be happy.)

- Will I have a helpful and supportive environment?

- What will I do during the summer?

- What will I learn? Will these things be useful after college?

- How will I pay for college? Will I be able to find extra money while I’m in school?

When I actually decided to study physics way back in the beginning of college, I actually hadn’t thought about most of these things. I guess I got lucky! I have found that physics can offer some great answers to these questions. But you don’t have to rely on chance, because you can learn from me.

Before I continue, I want to address a glaring question that you might have for me: “Why should I trust this guy’s advice?” The answer: because I know what I’m talking about! I studied physics for two years in high school (Spring-Ford Area High School), double-majored in physics and mathematics during college (Rutgers University – New Brunswick), and am now a physics graduate student (Cornell University).

Prerequisites

I think this might go without saying, but I’ll say it anyway just to be clear: you must really love the subject you choose to major in. If you didn’t like your physics classes in high school, you’re probably not going to be happy taking four more years of them in college. (Of course, it would make me feel better if you gave physics another try with a different teacher…)

You must also be willing to work extremely hard. The rest of this entry is going to focus on all the awesome aspects of majoring in physics, but please keep this in the back of your mind. Majoring in physics will not be easy. What I hope to do is to convince you that it will be worth it.

Why Should You Study Physics?

The short answer: it will make you happy. Lest you think I’m making stuff up, I actually have proof. The American Institute of Physics (AIP) keeps statistics on everything you could possibly want to know about the world of physics: employment, salary, education, etc. Some of the most interesting are their “happiness” statistics. In one of them, survey participants are asked whether or not they agree with the statement “if I had to do it all over again, I would still major in physics.” The results are shown below. If you look closely, you’ll see that on the right side, I included the only other major that I could find similar data for: sociology. If you know of any other similar surveys, please let me know about them so I can add more data points! (Sources: http://www.aip.org/statistics/trends/reports/fall08b.pdf and http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2010/08/17/asa)

A similar (but slightly different) AIP statistic measures the percentage of people with physics bachelor’s degrees that are satisfied with their careers. The two figures below compare physics to other majors. (Sources: http://www.aip.org/statistics/trends/highlite/emp2/figure5a.htm and http://finance.yahoo.com/news/pf_article_111000.html )

The big differences between physics and other majors in both of these surveys may reflect some differences in the survey methods. The point of these numbers is not to put down other majors; it is to show that many people (including me) find physics to be a very rewarding path to follow. The rest of this article will be an attempt to explain why so many people are happy with their physics degrees. If you’re thinking about a major other than physics, it might be a good idea to contact some people who took the path you are considering. Notice how many are enthusiastic and happy. If you’re having trouble finding satisfied people, you might want to pick a different major.

And so now we move on to the long answer, in which I will explain why and how studying physics in college will make you happy.

Will You Have Help?

One thing that really sets physics apart from other majors is the supportive environment. First, take a look at the number of bachelor’s degrees awarded each year for a few different majors. (Source: http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf11316/content.cfm?pub_id=4062&id=2)

Notice how the physics numbers compare to the giant majors like biology and psychology. (Also keep in mind that biology and psychology are small compared to juggernauts like business and communication.) This has huge consequences. Our brethren in the large departments spend their years in enormous classes. Their professors (occasionally) actively try to fail them in order to thin out their ranks. They often cannot develop personal relationships with their professors. On the other hand, physics majors get a lot of individualized attention from professors that genuinely want them to succeed. I suppose I can’t speak for every school, but at Rutgers, I got advice and support from the physics department head, my research advisor, most of my course professors, and older students. Whenever I applied for anything, I always had more good recommendation letters than I needed because I was able to meet so many professors. College is much easier to succeed in when you have other people helping you to do it.

Another fairly unique aspect of physics is the existence of physics education research. Many schools, including Rutgers, have research groups entirely devoted to teaching physics more effectively. (For example, see http://paer.rutgers.edu/.) They use psychology, cognitive science, and philosophy to find the best ways to teach physics. Even if your school doesn’t have one of these groups, there is a good chance that at least some of your professors will be using new techniques that will help you learn better. This is awesome! I won’t say any more here because I will probably be writing about it in some depth later.

How Will You Spend The Summer?

While your friends are at home working at Target, you will be getting paid to play with expensive and powerful physics equipment like liquid helium, lasers, radioactive materials, electron microscopes, etc. What more could you ask for? As an example of what your life could be like, I did astrophysics research during the summer after my freshman year (at Rutgers), accelerator physics research during the summer after my sophomore year (at Cornell), and condensed matter physics research during the summer after my junior year (at Rutgers). (I decided to take it easy after senior year.) In general though, you won’t just be having fun over the summer; you’ll also be building your resume and preparing yourself for post-graduation life. This lesson applies no matter what major you pick: you need to make sure your choice of major will prepare you to do something (go to grad school, get a job, etc) when you are done in college. This is not optional. In future posts, I will elaborate on my own research experiences and explain how to find some for yourself.

What Will You Learn?

The real value of a physics degree is, perhaps surprisingly, not the physics knowledge. Physics knowledge is only useful in certain set of circumstances. (It is really cool and very useful in a lot of circumstances, but not all.) The most valuable thing you will learn as a physicist is how to appropriately respond to confusing information. You will deal with abstract word problems in your classes and large amounts of data in your research. You will convert these difficult objects into equations and statistics that can be clearly understood, and you will use the results of your analysis to make judgements. These skills can be applied in any situation or job. Along the way, you’ll pick up a bunch of side benefits too: communication skills, computer programming abilities, efficiency, logic, and advanced math. Again, if you don’t believe me, I have proof. The next three figures show scores on three standardized tests: the Graduate Review Examination (GRE; required of anyone going to graduate school), the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT; required of anyone going to medical school), and the Law School Admission Test (LSAT; required of anyone going to law school). (Sources: http://www.ets.org/Media/Tests/GRE/pdf/5_01738_table_4.pdf and http://www.aip.org/statistics/trends/reports/mcat2009.pdf)

Care must be taken when interpreting these numbers. Very few physics majors (a few hundred) take the MCATS and LSATS, and these are probably very motivated and intelligent students. On the other hand, thousands of biology majors take the MCATS and thousands of political science majors take the LSATS. There are bound to be lesser-quality students among them. I’m sure that if you were to compare the scores of 200 most motivated students from each major, they would be essentially the same. As before, these statistics are not supposed to imply that physics majors are better than anyone else. Instead, they show that the skills acquired while earning a physics degree have applications outside of physics itself. For more examples of physics skills being useful in other areas, you should check out this page about “hidden physicists”. If you’re considering another major, ask yourself if it leaves your options open and teaches you widely useful skills.

The methods by which you learn are important too. Physics classes tend to focus on thinking ability rather than memorizing facts. On tests, you will be asked to apply your knowledge in new situations instead of just regurgitating things that the professor said. This is good for you: your friends in organic chemistry will spend endless hours memorizing chemical structures, but you’ll only have to learn a few formulas. When it comes time to prepare for a test, it is better for you to sleep (so your mind is sharp the next day) than to stay up all night stressing about benzene rings and whatnot. The physics route is difficult, but it is far less time-consuming and stressful if you handle it the right way.

How Will You Pay For College?

There are tons of ways for a physics major to get extra money during college. These include:

- Scholarships from your college

- Scholarships from your physics department

- Scholarships from national organizations

- Scholarships from the government

- PAID internships

- PAID tutoring

You can have all of these if you just reach out and take them! These money opportunities are not available to all majors. If you’re considering another major, ask yourself how much it will cost and if there are any ways to reduce your debt. I’ll explain later how to go about using these great sources of money.

A Few Loose Ends

There are a few ways to study physics in college. Each school usually has a “general physics” option for students who want to study physics but don’t plan to have a career in it. This is contrasted by the “professional physics” option, which is primarily for students who want to continue on with advanced study (either a Ph.D. or a Master’s degree) in physics. The professional option is sometimes further subdivided into specialties like astrophysics, biophysics, or ocean physics. Finally, there is often a five-year engineering/phyics master’s program or a five-year physics education master’s program.

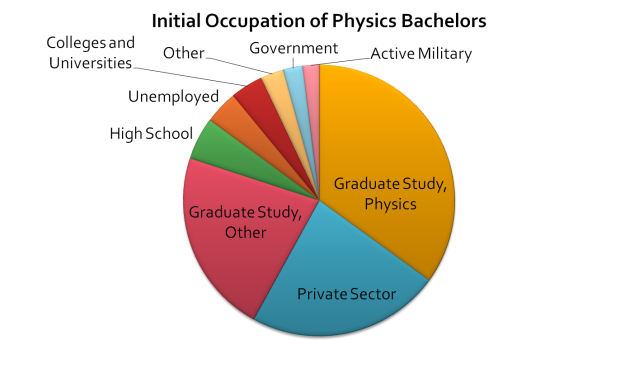

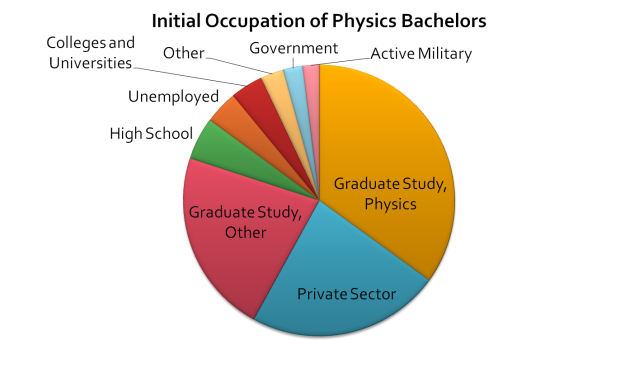

There are also a quite a few options for what to do after college graduation. The relative popularity of each is shown in the graph below.

Conclusions

College is a time-consuming and expensive undertaking. Your choice of major should not be taken lightly. You need to make sure that your chosen major will be fun, will prepare you for the outside world, and will not leave you drowning in debt. If you are so inclined, physics can be all of these things and more.

Further Reading

For more thoughts about the relative merits of various college degrees, see:

For more physics statistics, see: